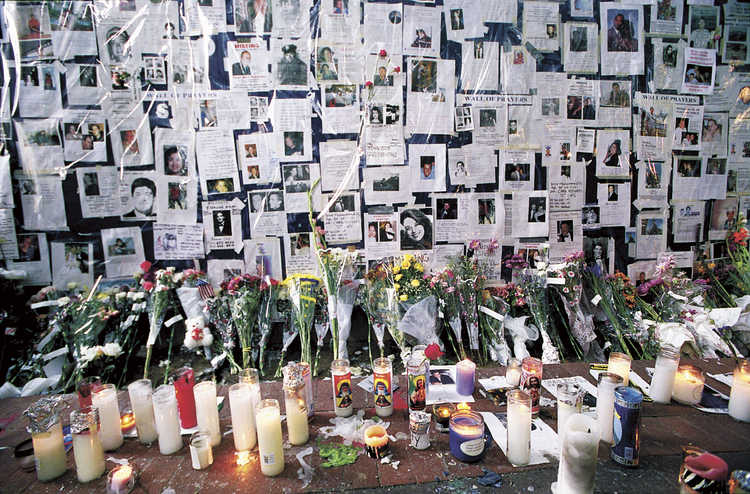

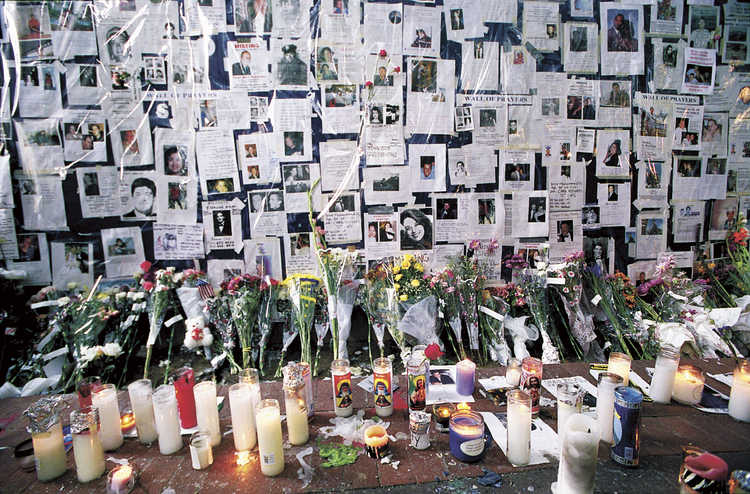

Claudia Alick’s 9/11 Street-Poetry Project is a testament to the resilient spirit of New York City in the face of adversity. Claudia, who was in New York during the tragic events of 9/11, channeled her experiences into a profound artistic endeavor.

Access the 9/11 Poems

here

In the aftermath of the attacks, Claudia volunteered with the Red Cross and then traversed the city streets, collecting exquisite corpse style poems that captured the diversity of emotions of a traumatized community. A decade later, Claudia returned to New York, this time including the solemn grounds of the 9/11 Memorial, to continue her mission. Gathering more poems, she documented the evolving emotions of a city that had learned to carry its grief while never forgetting.

The project, originally planned to continue in 2021, was thwarted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Nevertheless, Claudia’s work resonates as a testament to collective mourning, healing, and reflection. The poems she collected serve as a living record of the community’s indomitable spirit.

In the poetry of the community, we find the essence of New York’s resilience and unity. Claudia Alick’s 9/11 Street-Poetry Project not only commemorates a significant moment in history but also underscores the power of art to heal, remember, and inspire hope in the face of tragedy.

From “Dada & Surrealist Art,” by William S. Rubin, Harry N. Abrams, Inc., New York 1968

Among Surrealist techniques exploiting the mystique of accident was a kind of collective collage of words or images called the cadavre exquis (exquisite corpse). Based on an old parlor game, it was played by several people, each of whom would write a phrase on a sheet of paper, fold the paper to conceal part of it, and pass it on to the next player for his contribution.

The technique got its name from results obtained in initial playing, “Le cadavre exquis boira le vin nouveau” (The exquisite corpse will drink the young wine). Other examples are: “The dormitory of friable little girls puts the odious box right” and “The Senegal oyster will eat the tricolor bread.” These poetic fragments were felt to reveal what Nicolas Calas characterized as the “unconscious reality in the personality of the group” resulting from a process of what Ernst called “mental contagion.”

At the same time, they represented the transposition of Lautrééamont’s classic verbal collage to a collective level, in effect fulfilling his injunction– frequently cited in Surrealist texts–that “poetry must be made by all and not by one.”