As an autistic woman of color listening to conversations around autism in the workplace, I ask myself, where are all our voices? Where are the discussions on how cultural norms add complexity to our understanding of autism? I would like to explore our understanding of autism and how ideas of what is normal affects prescriptions of behavior.

I am a queer, autistic woman of latine-native immigrants. I am firmly at the intersection of woman, minority, and neurodivergent where there is very little room for authenticity and self expression. My purple faux-hawk, bold print blazer, and big jewelry do not fit into typical definitions of “work-appropriate”, especially not for an interview (to say nothing of how my autism affects my prospects). Yet that is exactly how I dress for interviews, even though there are a slew of studies showing how personal bias affects the likelihood of people of color being hired with all other factors being equal.

Right now you may be asking yourself, why take the risk? Like many women who deviate from what is expected of them – I risk my livelihood, my safety, and, at times, even my life, simply by existing as I am. So you must be wondering, why do it? I do it because if a woman’s behavior differs from the norm in the slightest, it is weaponized against us in the workplace, and I want to know upfront if my employer plans to stunt my professional progress by labeling me “unprofessional” before I have even started.

Am I a Know-it-all?

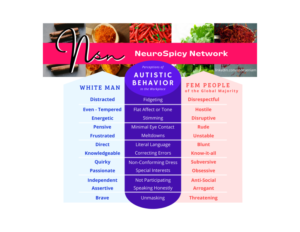

Imagine your co-worker walks into a meeting, doesn’t bother with pleasantries, and cuts off chatting to push the agenda forward. What gender did you imagine that person? Did that change your perception of their behavior? Now how would that perception have changed if they were a racial, ethnic, or disabled minority?

A former CEO, upon seeing me for the first time in person, asked me “Did we hire you like that?,” gesturing at my purple hair. He said the quiet part out loud! My response to this microaggression? “If you don’t want me for my skills and expertise [in biochemistry & data analytics] because of my appearance, then this is not the kind of company I want to work for.”

The color of my skin, the way my hair grows naturally out of my head, my very expression of self, is automatically considered subversive because it makes people uncomfortable that I choose not to conform. White Supremacy Culture calls this “right to comfort”, blaming someone else for the discomfort you feel at something unfamiliar. I couldn’t advocate for myself like this in my 20s when I was living paycheck to paycheck, drowning in student debt. It would have left me jobless, homeless, and dependent on support from a system that would see disabled people struggling rather than thriving. As autistic women, we MUST comply or be targeted.

Like many autists, I am logical, literal, and direct. In a world that considers this rude when coming from a woman, in men it is viewed as having exceptional leadership qualities. When coming from women of color, it is seen as hostile. My pattern recognition means I spot errors easily but, when I point these out, I am a know-it-all or a snob. When my male colleagues mention errors, they are considered knowledgeable and well respected for it.

The Fidgeting of an Autistic Adult

Playing with toys to focus (fidgeting), rocking back and forth to remain seated (stimming), repeating phrases (echolalia), are all behaviors that I suppressed in school to stay out of trouble. I still have to hide it in meetings today. The concealment of these normal behaviors is called masking. These natural behaviors help us with emotional regulation as well as help us reset our nervous systems from sensory overload. Though I have displayed many of the typical traits of autism my entire life – and have spent time around professionals that should have identified me – like so many women I was missed because of exceptional mimicking and masking. Autistic women are not afforded the grace that men are allowed to fail at the performance of being “normal.” The longer we suppress our need for regulation the more dysregulated we become, leading to meltdowns, and ultimately burnout.

Autistic burnout is not your regular burnout. In autists, this exhaustion can cause loss of skills, loss of speech, loss of connection to the body. While society sees autism as an unfortunate disability, I see it as just another variation of the human experience, and science agrees. Disability is not a word to describe people with physical or mental limitations, but rather disability describes the limitations created by design. We wouldn’t call people with blue eyes disabled because there are less of them in the world than brown-eyed people. Eye color doesn’t matter to a blind person in a world built for those with sight.

According to clinical psychologist, Dr. Martine Delfos, autism is mostly a difference in the speeds of development; meaning the cognitive development of the brain in autistic people is faster than the social-emotional development.

Autism is not a bad word

Being outspoken at work about the struggles of being a woman in the workplace does come with some risks: denial of promotion, dismissed or stolen ideas, our needs being minimized or ignored. However, the risks of being outspoken about being autistic as a woman of color, prove to be a lot more insidious. I was diagnosed autistic at the end of 2021 and I am outspoken about it, despite warnings of the dangers of doing so. Dangers like losing our autonomy as an adult in the form of medical kidnapping or being dependent upon unsupportive people or systems because finding employment is so much more difficult for an autistic person. These consequences are more dire for autists of color. In 2020, Drexel University Autism Institute reported twice as many white autistic adults (66%) were able to obtain work compared to black (37%) and hispanic autistic adults (34%).

The stigma of autism adds to the pathologizing of our behavior. I remember as a young girl having to practice facial expressions and rehearse conversations. To this day, I still have to think about my body language in every interaction: make enough eye contact, remember to mirror facial expressions, don’t stim, nodding at what you agree with, laugh when they laugh, make sure to pause between sentences to give them time to react. It’s exhausting! We are not allowed to exist as we are, much less behave naturally in the workplace.

The Bootstrap Fallacy

“Pull yourself up by your bootstraps” is part of the American mythos wherein “if you work hard enough, you can achieve anything”, but this is a myth that ignores the reality of the systems that guide our lives. I am a perfect example of this. As a first-generation American, my poverty looked like my parents arranging for the bus driver to drop me off at a local bodega because we were homeless. My loneliness looked like not having friends because I didn’t understand social cues that weren’t explicitly explained to me. My trauma looked like having to take care of my family of nine without anyone taking care of me. Yet, today, I am thriving because I have been able to design a life around my support needs. Not everyone has the luck or capacity to do this on their own. I am not an exemplary, I am a cautionary tale; a canary in the coal mine of the systems working as designed to make sure very few succeed in life.

Even though autism is not a solely white experience, the conversations about autism are still very much a predominantly white space. What’s new? Not fitting in anywhere is a common experience for autists, but being a woman of color raised in predominantly white spaces, I don’t fit in at work and I don’t fit in with my culture. I am an outcast everywhere I go. As a latine-native, I have to contend with colorism, anti-indigenous racism, misogyny, and more from the colonization of my own culture; so how could I have been identified as autistic when I was masking so fiercely to survive?!

Community vs. Individualism

After countless social media groups, meet-ups and apps, I have failed to find a community where I fit in. So, I decided to build my own with the NeuroSpicy Networking Group on LinkedIn. It connects neurodivergent professionals, helps us tell our stories, and elevates our excellence despite the lack of resources for adults. We are breaking down the barriers of othering (us vs them) and helping people understand our commonalities. Despite not being diagnosed until later in life and not being supported, many autists are thriving because we are rebuilding communities.

My mission is to solve global issues by creating networks of people, organizations, and mutual aid groups to support and find each other. To that end, I co-founded the OneFreeApp.com Project, which aims to reconnect humanity with meeting its needs via community rather than commerce. It connects people with needs, to the people able to comfortably meet those needs, both locally and remotely, at zero cost to users. We want to create a world that centers the most marginalized people.

But, at every turn, we are met with resistance. Resistance to being heard, resistance to being included, resistance to being understood. We didn’t build these systems, but they are upheld by everyday people.

So, if you’ve made it this far, let me ask…

Would you see my fidgeting in a meeting as distracting or disrespectful?

As a manager, a recruiter, or as a co-worker, how are you upholding the status quo?

What are you doing to center the most marginalized person in the room, even when they are not there?

When jobs, buildings, and communications are accessible, the disability is diminished or eliminated. Think Universal Design, “design that’s usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialized design”.

Do not call us inspirational or brave. Instead, act on behalf of the most marginalized people, to help us get the support we need to thrive. Because when we thrive and can share our amazing gifts with the community – everyone benefits.

What Can I Do?

You may be thinking: I’m just one person. How can I do anything about this?

Your actions and words have an impact, whether you know it or not.

Here are some things you can do to help.

Look at your expectations:

When you see someone doing something that you find odd or that doesn’t seem “professional” at work, ask yourself, is it harming anyone? Is the aversion you are feeling due to discomfort because it doesn’t fit your definition of normal? When you feel uncomfortable about “unprofessional behavior,” stop and think about what your expectations are, and about why you feel the urge to comment on someone else’s behavior or appearance. Stop and think before you speak.

Meet People Where They Are:

Don’t ask people to change their behavior to meet your expectations. Your story, your history, your struggles may be different from theirs. Be aware that words have impact, no matter how well meaning you may be. Ask yourself, is what I want to say needed? Would I want someone telling me that? Celebrate and support people who are different. Recognizing the common humanity of everyone is the first step in the celebration of our differences.

Advocate for accommodations at work:

What assumptions do you make about a person’s ability by looking at them? Attributing the need for breaks and rest to laziness is ableist. You can’t see a person’s energy levels, limitations, nor their disability. Advocate for everyone to have accommodations. This may look like allowing people to wear noise-canceling headphones in a meeting or bringing up that your entryway isn’t cleared of snow for users of mobility aids. This could be thinking about how color blind people may not be able to read your charts or how your Zoom meeting should always include closed captions.

People may not want to speak up because it can make them a target and people usually cannot afford to lose their job and their healthcare. If you can, speak up for those who can’t. If they are speaking up, listen and support them. A world built for the minority benefits the majority because more people are able to access knowledge, share ideas, and innovate. The better supported we are, the better everyone will thrive.

Author: Jesenia M.